Access to new treatments for carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections in Argentina: an urgent debt

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.52226/revista.v33i118.394Keywords:

public health, EnterobacteralesAbstract

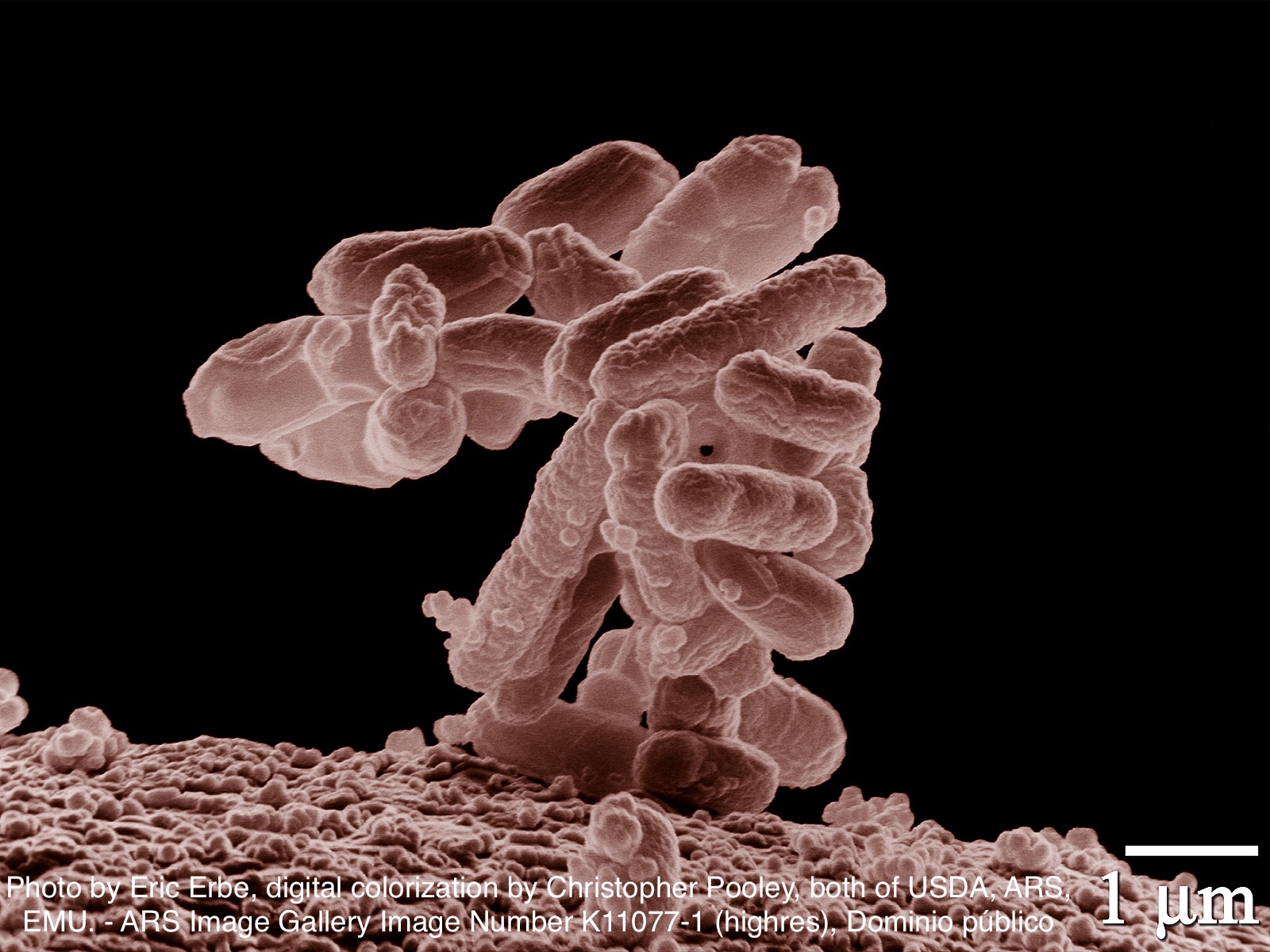

Infections by carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae represent one of today's greatest global public health challenges (1). These bacteria, resistant to multiple antimicrobials, are associated with high mortality and morbidity, especially when they present in the form of severe infections such as bacteremias, pneumonias associated with mechanical ventilation or intra-abdominal infections. The treatment of these infections has historically been limited to schemes with high toxicity such as colistin, antibiotics with suboptimal pharmacokinetics such as tigecycline or poorly-standardized combinations, often with unsatisfactory clinical results (2).

The introduction of antimicrobials including new β-lactamase inhibitors such as ceftazidime/avibactam has transformed the therapeutic approach to these infections. Several observational studies have shown a significant reduction in mortality with these regimens compared to traditional treatments, especially in critically-ill patients (2). At the local level, the prospective, multicenter EMBARCAR study demonstrated that the use of ceftazidime-avibactam, alone or in combination with aztreonam, was associated with a decrease in 30-day mortality, in contrast to other antibiogram-active regimens (3). For this reason, ceftazidime/avibactam is currently recommended as first-line treatment for these infections (4).

However, this important therapeutic advance faces a substantial barrier in resource-limited settings: access. In this issue of ASEI, Abusamra et al. present a critical contribution by exposing the national situation regarding access to ceftazidime/avibactam in Argentine health institutions (5). The information was obtained through a survey of institutions participating in the Argentine Hospital-Acquired Infection Surveillance Program (VIHDA) and the Provincial Program for the Prevention and Control of Healthcare-Associated Infections and Antimicrobial Resistance of the Province of Buenos Aires.

A total of 199 responses were received from institutions belonging to 19 jurisdictions in the country, of which more than 70% belonged to the public sector. The results are as revealing as they are alarming. Only one third of the institutions surveyed had ceftazidime/avibactam available for empirical treatment, and only 64% had it available for targeted treatment. This gap widens when comparing between subsystems: while in the private sector empirical availability reaches almost 50%, in the public sector it barely exceeds 27%. Even for targeted treatment, access remains significantly lower in the state sector. The situation may be even more critical given that the public and private institutions evaluated may not represent the entire system, since many small institutions, where access to high-cost medicines is often even more limited, do not participate in the surveillance programs used as the basis for this survey.

The low availability reported in this study for both empirical and targeted treatment is not a minor finding. Most severe infections with carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae occur in critically-ill patients, in whom early initiation of effective treatment has a direct impact on survival (6).

While the study authors acknowledge that local epidemiology may justify in some cases the non-use of ceftazidime/avibactam, and that cost analysis was not included, the data suggest that economic constraint is a key factor.

This study reflects the urgent need for measures to ensure equitable access to last-line antimicrobials. Limiting their availability not only compromises clinical outcomes, but may also increase indirect costs due to increased toxicity or prolonged hospitalization associated with the use of less safe and/or less effective therapeutic regimens.

Finally, it is important to remember that the use of these high-cost antimicrobials should be carried out within institutional antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs), as well as in comprehensive infection prevention and control policies. Only in this way will it be possible to prevent new infections by multidrug-resistant organisms and preserve the efficacy of these vital and limited therapeutic resources.

Downloads